Memory: An Introduction. Why Now?

Your guide to understanding the memory industry

Everyday it feels that memory stocks are going up. Micron, one of the largest memory players, is up almost 3x in the past year alone. Many investors are stuck seeing similar names go up day after day, waiting for a pullback. However, they fail to really understand what the product really is.

In this piece, Nicolas and I are here to break it down in an easy to understand way to understand the opportunity at hand. Let’s get into it.

Intro

So what is memory and why is it so important?

Memory is what enables a computer or device to store information while ephemeral computation is being performed. This is done predominantly through read and write operations. Each layer of memory has different profiles around read/write speeds, cost and capacity.

In AI, memory has become even more important because models need to process massive amounts of data all at once. When we use tools like chatbots, image generators, or recommendation algorithms, memory is constantly moving huge datasets in and out at high bandwidths.

The more intelligent and capable AI models get, the more memory they need to function effectively. Without powerful memory systems, advances in Large Language Models and Machine Learning use cases stall.

The Memory Hierarchy (Storage vs Working)

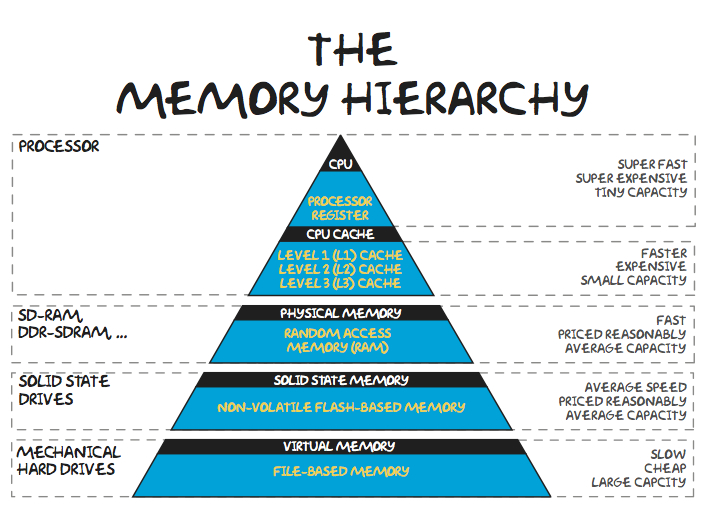

To better understand memory, we first need to break down the layers of memory.

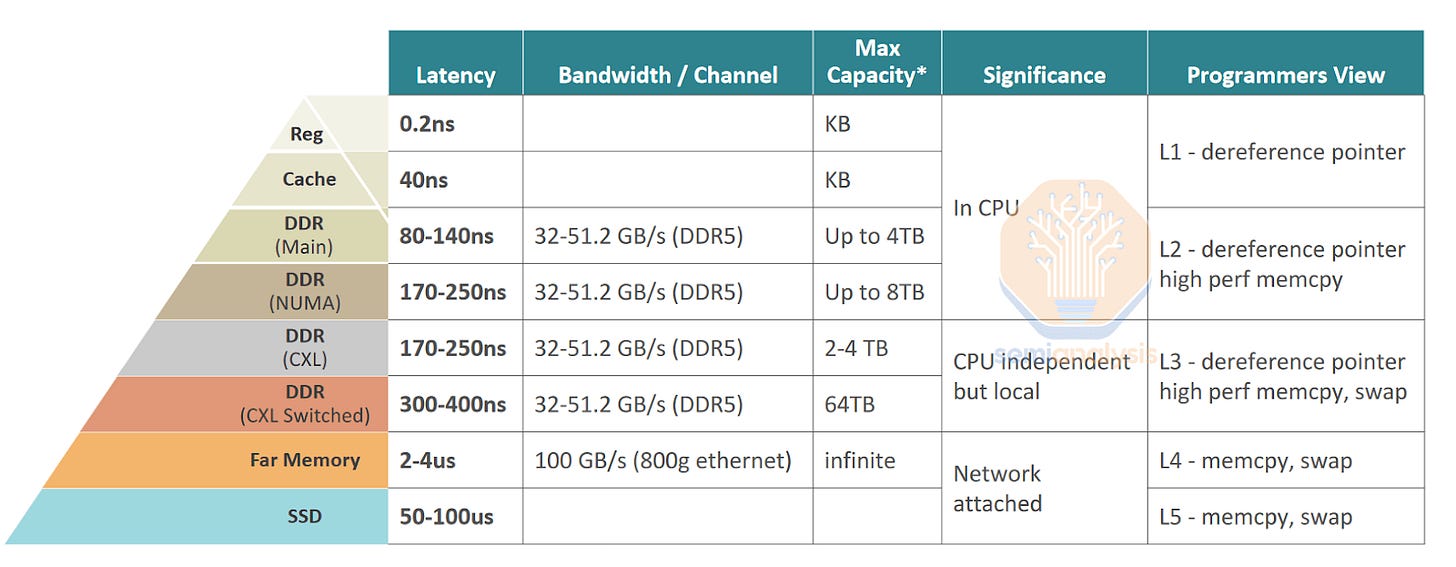

Computers split memory into working memory (used while the system is actively performing computations) and storage memory (used to save data long-term at the expense of slower read/write speeds). This separation exists as memory that is high bandwidth (low read/write times) is expensive, while long-term memory that is cheap, is lower bandwidth (high read/write times).

Many concepts around memory boil down to the distance that the chip is from the processing unit. The further the distance, the slower the throughput.

1. Processor Registers & CPU Cache (SRAM):

What it is: This is often the highest throughput memory in the entire system as it is sitting inside or right next to the XPU (XPU = CPU or GPU). It holds tiny bits of data the processor needs right now.

What it’s made of: SRAM (static memory built directly on logic silicon).

Cost & size: Extremely expensive per bit, tiny capacity.

Where it’s made: On the same chip as the CPU.

Key manufacturers: Intel, AMD, Apple

2. Physical Memory (DRAM / RAM)

Designated random access memory / Random Access Memory

What it is: This is the computer’s main working memory, the desk where active programs live. Throughput is required here as delays cause a queue of computations to occur.

What it’s made of: DRAM cells (one transistor + one capacitor per bit).

Cost & size: Somewhat expensive, medium capacity (GBs).

Where it’s made: Mostly fabricated in South Korea, Taiwan, and the U.S.

Key manufacturers: SK Hynix, Samsung Electronics, Micron

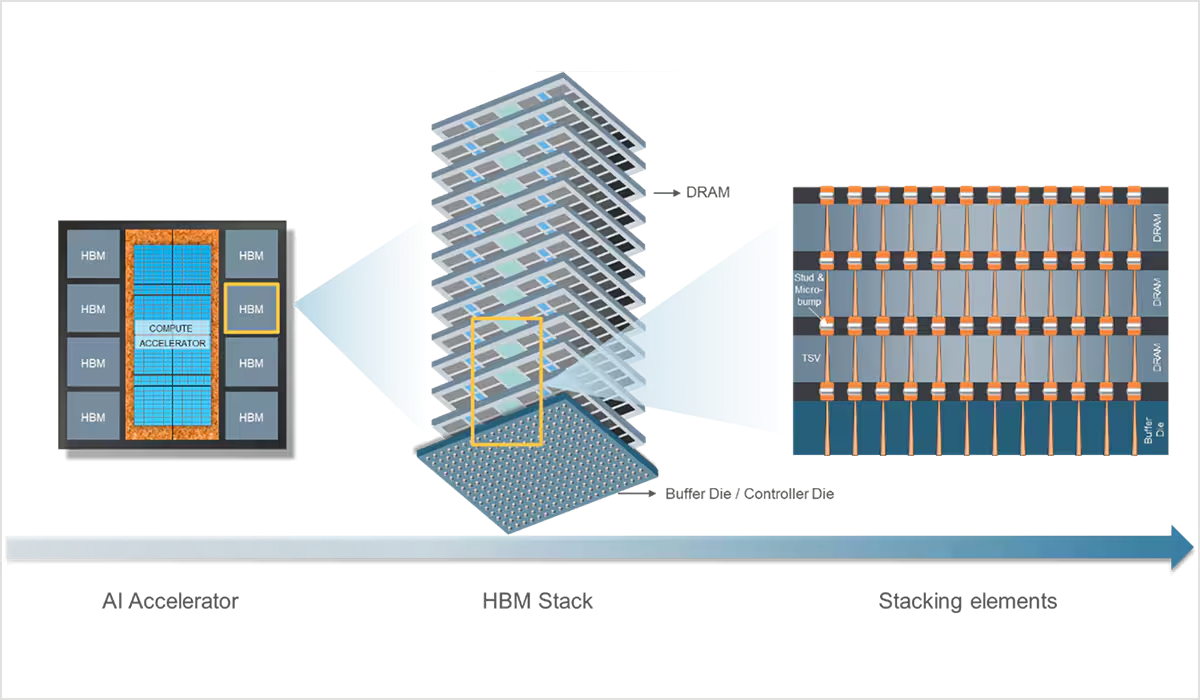

3. High Bandwidth Memory (HBM)

Specialized DRAM

What it is (simple): Ultra-fast DRAM stacked vertically and placed next to AI chips. Due to the vertical stacked nature of HBM, it has higher throughput at the expense of manufacturing complexity.

What it’s made of: DRAM dies stacked with through-silicon vias (TSVs).

Cost & size: Very expensive, smaller capacity relative to DRAM although much faster than it.

Where it’s made: Taiwan & South Korea due to the advanced packaging requirement (physical vertical integration)

Key manufacturers: SK Hynix, Samsung, Micron

4. Solid-State Storage (NAND / SSDs)

NAND is non-volatile flash memory that stores data without power, used in high-density storage devices like SSDs, USB drives, and memory cards.

What it is (simple): Long-term storage for files, apps, and data when power is off.

What it’s made of: NAND flash cells storing electrical charge.

Cost & size: Cheap per Gigabyte, large capacity (hundreds of GBs to TBs), lower throughput than HBM and DRAM but often sufficient for less latency critical computational workloads.

Where it’s made: Asia mainly (Korea, China, Japan).

Key manufacturers: Samsung, SK Hynix, Sandisk, Micron, Kioxia

5. Hard Disk Drives (HDDs)

What it is (simple): Traditional spinning disks for cheap bulk storage.

What it’s made of: Magnetic platters and mechanical parts.

Cost & size: Very cheap, physically large, slow throughput.

Where it’s made: Asia

Key manufacturers: Seagate, Western Digital, Toshiba

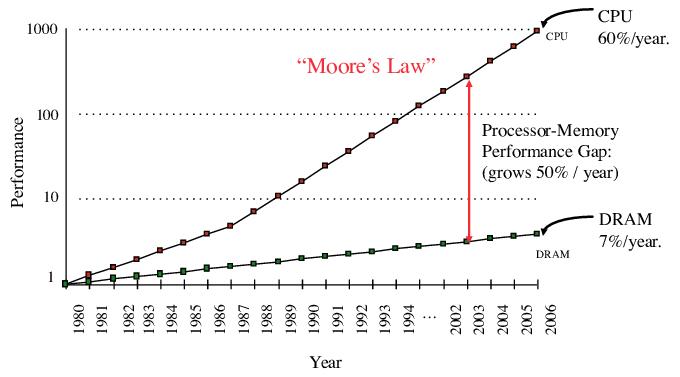

The closer memory is to the processor, the faster, smaller, and more expensive it gets, AI pushes demand toward the very top of the pyramid. This is due to the extremely parallel nature of GPUs that are performing trillions of computations per second.

HBM and NAND

HBM is the most critical memory layer as it sits directly next to AI GPUs, while NAND is the “warehouse” storage that holds datasets, model checkpoints, and logs.

In AI data centers, NAND-based SSDs feed data into DRAM/HBM, and HBM then feeds the GPU fast enough to keep the compute busy. LLM models utilise this tiered architecture of memory to ensure the most efficient use of all storage layers. However, the preference is always to have as much computation as close to the GPU as possible.

Over the past few years of the AI buildout, both have seen unprecedented demand. HBM demand is exploding because bandwidth is the limiter, while SSD demand rises because data inputs & outputs keep growing (training data, retrieval, inference logs). An often underappreciated fact about memory needs is the recursive nature of agentic workflows that consume compute resources as they call other agents, which call even more agents. Agentic activity can therefore lead to situations where demand scales beyond human induced demand.

Historically, DRAM and NAND have been viewed as commodities by investors and the broader market. This has meant that supply is monitored very carefully and matched to meet demand as it is needed. Overbuilding has dire consequences as semiconductor fabs are expensive to spin up and costly in their ongoing operations. Due to this nature, supply is gradually increased in the market to avoid an over build. However, as AI demand has exploded, very suddenly all forms of memory are becoming key bottlenecks and giving memory players significant pricing leverage over customers. This pricing leverage allows them to record sky high profits as they are the critical bottleneck in the AI supply chain. GPUs without memory are rendered useless. No computation can happen without memory. In order to understand why and how they can maintain pricing leverage, the next section talks about the technological moat they hold.

Memory Defensibility

What makes the memory players turn from commodity to the overlords of the AI race is their advanced specialisation in semiconductor manufacturing processes. These processes can be broken down into three key elements:

Manufacturing complexity (how to make the chips)

Yield (how many successful chips you make per batch)

Qualification processes (does the chip meet requirements for consumption)

The moat is a game of making billions of tiny cells reliably, at massive scale, with razor-thin margins. For HBM specifically, you need advanced DRAM and complex 3D stacking/packaging (TSVs, thermals, interposers) that only a few players can do at high yield, and customers must validate parts over long cycles.

It’s for this reason that there are only three companies that qualify in this game. Leadership shifts matter when one vendor ships next-gen stacks earlier as it gives them a distinct advantage in perfecting the manufacturing process of the next generation. HBM is also structurally premium-priced versus standard DRAM due to being co-packaged with the processor and not being homogenous like previous generations of DRAM (which were “commodities”).

Spinning up a memory company that can compete at the scale of the current players would take over two decades of expertise and north of $50b. China’s YMTC has been able to catch up in legacy DRAM manufacturing processes but has struggled to do it with high yields and without government support. They are also locked out of more advanced generation of semiconductor manufacturing capabilities due to material and technology export restrictions imposed by the United States. Furthermore, despite memory being “hardware”, there is still a chain of software in the form of chip firmware that requires deep integration. China or any other state players have to be able to overcome deep software lock ins in addition to all the other challenges that present. It is for this reason memory companies are far more defensible than any other point in their lifecycles.

Closing

Raw compute power has scaled faster than memory’s ability to move data, this is the “memory wall”. Chips can do math insanely fast, but they stall if data can’t reach them quickly enough.

A lot of time and energy goes into shuttling model weights and activations between memory and compute, not the math itself, so bandwidth becomes the limiter.

HBM is the current best workaround because it puts wide, fast memory right beside the GPU, but it’s capacity- and supply-constrained, so memory ends up setting the pace for how quickly AI systems can scale.

What we’re experiencing right now is a set of 10 or less companies that hold the manufacturing specialisation to develop memory chips that power the future of AI which isn’t just a matter of productivity, but slowly national security as these chips enable next generation warfare to take place.

If you believe:

a) AI is here to stay

b) AI’s demands will only increase over time

Then the future belongs to these 40-50 year old companies that have been making “commodities” that are now the core bottleneck in the AI build out. Their immense pricing power has already allowed them to start extorting many companies downstream in their supply chain and we believe that this trend will continue to extend, impacting their customers’ margins.

We are at a point of structural change in the world and memory may well be one of the earliest signs of this new world order.